Cawthron Institute achieves scampi farming breakthrough

20 April 2016

Cawthron Institute aquaculture scientists have succeeded in raising the world’s first New Zealand scampi in captivity, taking New Zealand a step closer to establishing a scampi aquaculture sector.

The scientists recently hatched eggs from the high-value crustaceans and raised them to early adulthood – a significant breakthrough for the Government-funded 6-year research programme.

“The project is only two years old, but what we’ve learned about the scampi in terms of husbandry and behaviour is significant,” Cawthron aquaculture development specialist Kevin Heasman says.

“Prior to this programme, our knowledge was very limited. Only the first larval stage had ever been recorded and that was in 1976 so we didn’t know how to raise them and what was required in terms of eggs, feeding, aggression or any of that.

“To date, we’ve managed to recover eggs from wild-caught females and hatch those eggs in our nursery and take those eggs through all of their larval stages and into the post larval stage. Now we’ve got animals that are six months old and about 30mm long.”

The scientists are working alongside Waikawa Fishing Company, University of Auckland and Zebra-Tech on the research programme, which is aimed at developing more sustainable and commerciallyattractive harvesting methods for New Zealand scampi (Metanephrops challengeri) and establishing land-based aquaculture systems for scampi production. It is the world’s first captive breeding programme for the species.

Metanephrops is a genus of clawed lobsters, commonly known as scampi, and found around the world. The New Zealand species is a deep sea scampi, endemic to New Zealand waters. New Zealand scampi grow up to 30cm long and live in small burrows on the continental shelf in waters between 200-500 meters deep. The 789 tonnes of the product harvested by trawling last year generated $17.6 million in revenue making it an attractive proposition for a potential new aquaculture species.

“If we can successfully take wild caught egg-bearing females and raise those eggs, or even let the female raise them through to harvest size – there’s an entire industry right there,” Mr Heasman says.

“It’s less wasteful and you end up with animals that are in optimal condition which results in a very high quality product. What we don’t know how long it will take to grow to a market size. At the moment, there is actually no way to tell how long it takes the wild scampi to reach harvest size either.

“At the end of the day, it will come down to how long it takes to grow an animal to a good marketable size and what the value of the animal is at that size and then we can start working on improving the economics of it.”

“We will begin to learn more about their growth rates as the research continues but at the moment the focus is on maximising larval production and growth rates. This year we’ll be focusing on dietary requirements and temperature and aiming to create the optimal growing conditions,” Mr Heasman says.

“We’ve got a long, long way to go, but compared to two years ago, we’ve already come a long way. Some people work on a species for years and never get past the larvae stage, and we got the larvae through in the first year. While there is a lot more work to do; we’re very excited about the potential for this species.”

Previous News

Read previous news story Scampi programme launch

Watch the story about this research project which aired on Maori Television’s Project Whenua (episode 9)

For more information about this programme contact:

Kevin Heasman, Aquaculture Scientist (Species Development & Enhancement), Cawthron Institute.

For media enquiries please contact:

Megan Kitchener, Communications Manager, Cawthron Institute.

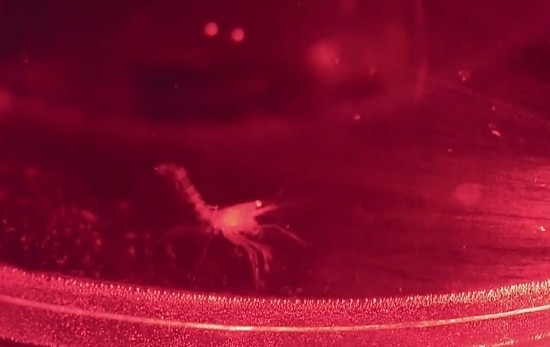

New Zealand scampi.

One of the first New Zealand scampi raised in captivity. Scientists at Cawthron Institute used an infra-red camera to capture this image as the deep sea creature is sensitive to light.