He kāinga rangahau: Developing a framework for research that is just and equitable for indigenous peoples.

By Heni Unwin and Te Rerekohu Tuterangiwhiu

September 2021

This opinion piece was originally presented as a keynote address at the recent ANZMBS conference.

Introduction

It may come as a shock for some to hear, but Māori who work in science are almost always working in an environment that is culturally unsafe for them. It may also come as a shock to hear that science, though it takes a lot from indigenous peoples, often fails to serve them.

Cultural safety has many definitions, but generally speaking it is an environment which is spiritually, socially, emotionally and physically safe for people because they are protected from harm and their identities and needs are understood and embraced.

Māori scientists are not culturally safe in this country, just as Māori are not culturally safe in this country, and we believe the time has come for change. We are excited to be part of a movement to make research equitable and just for indigenous peoples, starting at home in Aotearoa with the development of ‘He Kāinga Rangahau’, a framework for research that is equitable and just for indigenous peoples who have been colonised.

This framework has been developed by Cawthron Institute’s Te Kāhui Āio group of Māori researchers and cultural and business development advisors. Although it was born out of our own internal reflections about how we want to see Cawthron embrace Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview) and truly partner with Māori, we also see it as being a framework that could have national and global impact.

Engari, before we explain what the framework entails, there needs to be greater understanding of Te Ao Māori identity and culture and the challenges Māori have had to face, not only within the science sector, but historically in New Zealand.

Heni Unwin and Te Rerekohu Tuterangiwhiu. Image credit: Royal Society Te Apārangi.

Heni Unwin and Te Rerekohu Tuterangiwhiu. Video credit: Royal Society Te Apārangi.

1. Understanding Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview)

Māori people have a deep connection to the physical world around us through our whakapapa, or genealogical history, and our story of creation. Through whakapapa we are related to all things by placing objects, organisms and people’s relationships in the world. We have physical and spiritual links to mountains, rivers, oceans and animals – they are our whānau (family). We share the same origins, evolution and history, as well as a shared future. Atua are not merely mythical gods, but source points of life and they are our ancestors. It is this whakapapa that reminds us of our connection to other species and reminds us that we are, in fact, younger siblings to everything surrounding us.

This relationship to the natural world and atua provides us with connection, meaning and purpose, and instills in us a deep sense of responsibility. We are part of an unbroken line that has a responsibility to manaaki (enhance the mana of) the things that support and give mana to us. This is considered across space and time, and it’s not possible to disregard the impact of actions now on future generations.

Then there is the social world and its many levels. We start with the whānau, or nuclear family of connected individuals (which can also be used broadly in the same way that family can be used, i.e. Cawthron whānau), then the hapū which are extended groups of families that form sub-tribes who descend from eponymous ancestors, and then the iwi, which is a larger contemporary tribal group made up of hapū groups and sometimes smaller sub-tribal groups, all connected by space, time and genealogy. It’s very important to note that iwi, hapū and whānau all have their own unique mana and authority within the same all-encompassing social constructs and this is also anchored to physical spaces, rohe and cultural boundaries. Furthermore, all social levels are continuously connected and play active governance, management, and operational roles within the wider social fabric of Te Ao Māori.

This is an extremely brief summary of the factors that shape the Māori worldview and identity. We want to be clear that from our perspective, meaningful and positive engagement with Te Ao Māori is done with the awareness of these many connected social factors, so that researchers (especially our own Cawthron whānau) are informed when they engage with Māori and know how to connect appropriately. This is how we understand ourselves.

It is a constant struggle for Tangata Whenua to remain themselves without compromise in this changing world, without giving away more of themselves than they already have.

We would also like to acknowledge indigenous people all over the world who are fighting to protect their knowledge and way of life. Our stories are not the same but our challenges are aligned and we call on non-indigenous researchers in Aotearoa and worldwide to consider how they can create a space at their table.

As Māori researchers, we are asked to draw on very personal parts of our identity in support of our work in a way that other researchers are not. This often involves compromising our integrity by being asked to force our culture into tick boxes to get funding, or to retro-fit cultural practices into research, or watch short-term research projects deliver on their objectives without really making a long-term difference to the communities they were supposed to be helping. It’s a process that could be described as de-mana-ering. Mana is power and standing and being a Māori researcher is all too often disempowering. We continuously have our identity, our wai, whenua and moana stripped away as western knowledge systems draw upon concepts from Te Ao Māori for the benefit of science, without delivering benefit to Māori.

Then, to top it all off, we have to deal with ignorant perspectives like this – Scientists rubbish Auckland University professors’ letter claiming Māori knowledge is not science – NZ Herald – senior academics at New Zealand’s biggest university questioning the validity and value of Mātauranga Māori.

But that’s just within the science system – there’s still the broader context of what Māori have suffered due to colonisation, and the ongoing burden of the injustice and harm that process caused.

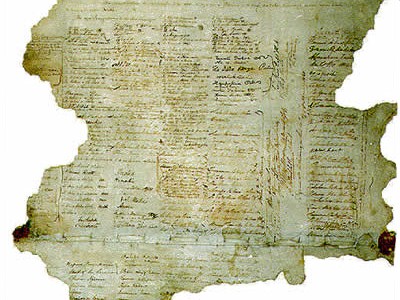

We are really lucky in Aotearoa to have Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi), which has concepts that are anchored within it that outline the rights and responsibilities of both Tangata Whenua (Māori) and Tangata Tiriti (everyone else) as a partnership. However, people rarely acknowledge the cost of the “partnership” to Māori and what the mechanisms of this partnership were. A lot has happened since that time that has not been consistent with the principles of Te Tiriti and partnership. There was a real cost to the partnership, and Māori have paid it almost exclusively.

In 1862, the Native Lands Act initiated turmoil within Māori communities by causing displacement, inequity and poverty. In 1863, the New Zealand Settlement Act enabled the confiscation of Māori land by the government. Māori were instantly not safe in their own spaces anymore. There were many other laws passed that affected Māori land rights, including the Public Works Act, which created physical poverty for many Māori for the first time in their intergenerational legacies or in the history of this country.

The Native Schools Act of 1867 created a language bias, a knowledge bias, and an unnatural way of transforming ideology and people. It is common knowledge that Māori children were caned and beaten for speaking Te Reo Māori in schools. That didn’t just mean Māori couldn’t speak words in their own language, it also meant they couldn’t think the way they thought. Language shapes thought in so many ways. This was one of the most violent and oppressive acts of colonisation Māori endured in the promise of partnership. Later on, the Tohunga Supression Act of 1907 continued that knowledge bias through the criminalisation of Māori knowledge practitioners.

The mechanism of transformation in Aotearoa was ‘brutality’ and it occurred within the context of our knowledge system. The implications of that for Māori within the academic knowledge systems are enormous. This has led to us feeling unsafe in our own lands.

The irony in the current day, is that these very practices and our way of thinking are sought after and so necessary to the health and wellbeing of people in Aotearoa. The science system is now seeking out ‘systems-based’ approaches from within Te Ao Māori that were previously dismissed. However, the expectation that Māori would have an intact knowledge system that could rival that of an imperial, academic knowledge system, after continuous legislation that chose to brutally discredit it, creates a frustrating and ongoing bias.

So, now that you know a small part of the struggle, the injustice, and the difficulty Māori face within the research and science system and in wider society, we ask you to consider, who are you in this context and what are you going to do about it?

The first answer is quite simple – if you are not Māori, you are ‘Tangata Tiriti’ – a person of the treaty. This means anyone who has come to Aotearoa before or after the signing of Te Tiriti who does not have Māori whakapapa.

On the next question, we can only offer some guidance. We’d encourage some reflection: Have you been a good partner? Could you do better at sharing power and control? How could Tiriti values better translate into Tiriti actions in your life? But what’s really required is action, because values only really exist if they’re acted out.

Image: Ministry of Culture and Heritage. ‘Read the Treaty’, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/treaty/read-the-treaty/english-text

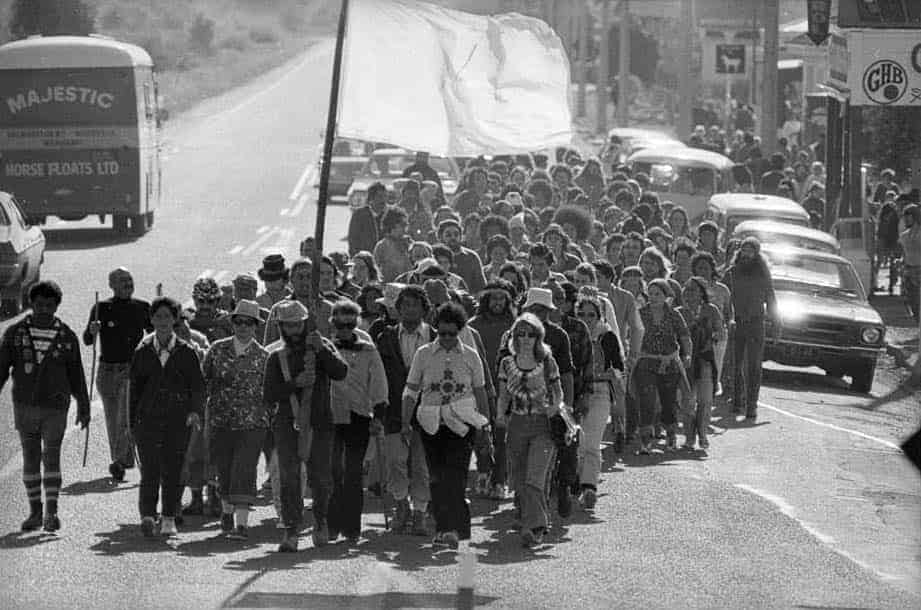

Image: The Māori Land March on the outskirts of Palmerston North, October 1975. (Alexander Turnbull Library. Reference: EP/1975/4202/8a-F)

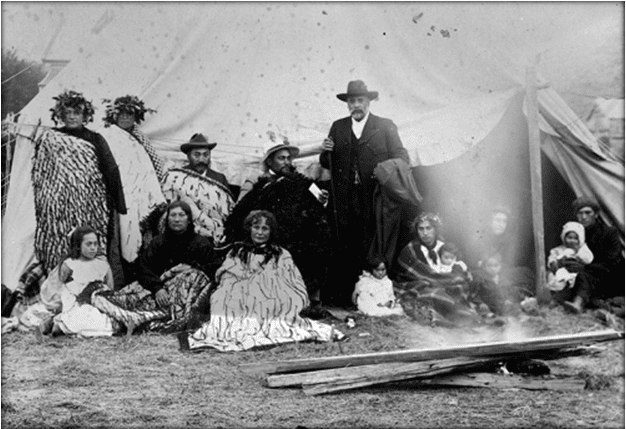

Whirinaki Native School. Image: Archives New Zealand. Department of Education. Archives reference BAAA 1005 Box 1

In the science sector, Māori scientists are in a constant struggle fighting this institionalised bias. We have been working for a long time trying to make a difference by developing a new framework for engaging with Māori in research, because we hear from our whānau, hapu and iwi that they are also tired. They want science to serve their interests and believe that the utilisation of Māori knowledge should provide benefits those who hold it.

This context is the basis upon which we want to build a kāinga (framework) for research, including practices and behaviours. We want to draw on the values in Te Tiriti, but also turn those values into appropriate partnership actions, so that the research is equitable and just to the indigenous perspective and reflects the pressures on indigenous people.

3. Building something better – A framework for equitable and just research

In this context, our team at Cawthron Institute have been looking at how Te Ao Māori and New Zealand’s research system interface and relate to one another. We decided to come up with a conceptual framework, embedded within the central concepts of Te Ao Māori, that could redefine how Māori engage and partner with the research and science systems in Aotearoa.

Our ‘Kāinga Framework’ is centered around the concept of ‘kāinga’ and ‘ahikā’, or traditional tikanga of establishing a home settlement. Kā is a spark of energy, it is also contextually referred to as the process of ‘ignition’. In Te Ao Māori, the concept of kāinga captures most of the values, principles and practices required for engaging and connecting with others. The one thing that was central to a home for Māori when they arrived in Aotearoa, and for a long time afterwards, was fire or ahi. In particular, keeping the home fire lit or ‘kā’ was a practice of occupying space, generating knowledge and innovation and keeping the kāinga (home) a functional, liveable and safe place for hapū to be together. There were established kawa, tikanga concepts and practices relating to keeping fire in the kāinga that we can draw upon for this framework. If we want research spaces to be safe for Māori, this is where we need to start.

‘1. The first is ‘Te ahi kō mau’: The internal flame where everything originates. This principle is about understanding our origin, culture and identity and being true to it in everything we do.

This concept is paired with a corresponding consideration – Kō te mauri-ora o te whenua kāinga – this literally means the life source which originates from the womb (of Papatuanuku) in which the kāinga exists. In a research sense, we interpret this as effort towards understanding original natural environmental baselines, when designing environmental research. This requires meaningful engagement and in-depth discussion with Māori about what their aspirations and reflections are before the project begins.

2. Next is ‘Te ahi kā roa’: This is the fire that is always burning. The ahi was continuously kept and maintained by the cultural responsibilities and behaviour known as ahikā. This kaupapa focusses on the tikanga, ritenga and kawa (customs, rituals, and practices) that each hapū and kāinga administered through generations, through time and space, by nurturing the ahi – how to literally keep the fire burning, but also how to maintain the health and wellbeing of those within kāinga. This also includes the protocols for how kāinga should connect and interact with other kāinga.

This concept is paired with the consideration of rangatiratanga (sovereignty/autonomy). It encourages us to consider how we should engage with Māori at the appropriate level. What are the customs, protocols, and practices that should be considered when doing so? We should also consider the likely impact of this research on the kāinga, and whether it will benefit the people who live within it.

3. The next concept is ‘Te ahi kā pura’: This refers to the invisible flame. Often this is metaphorised as ‘mātauranga tuku iho’, or ancestral wisdom that is passed down through legacy. This concept encourages us to draw upon the knowledge that has been passed down through generations, treasure it and use it in the present, build on it and transfer it to younger generations so that it lives on.

This concept is paired with the consideration of how to practice manaakitanga, which can be defined as mana enhancing behaviours and actions that place equal or greater importance on the wellbeing of others than one’s own self, through the expression of aroha, hospitality, generosity and mutual respect. The hau kāinga (home-people) look after their own and share knowledge that enables them to care and provide for all that live there.

Image: ‘Picturesque New Zealand’, by David Paul Gooding. Original caption: A Maori Village. 1913.

Image: ‘Maori village’, c1909. Pataka Museum Collection, Porirua Library ref P.2.132.

4. The final concept is ‘Te ahi kā mai tawhiti’: An unbroken line of connection between the fire of the present and its original spark that established the kāinga. This concept is about maintaining an unbroken connection through time and space.

This concept is paired with the consideration of whakapapa and encourages us to draw upon our identity and history, and act on our responsibility to future generations. This requires us to plan future generations into our present, so they are well equipped for the future. We do this through intergenerational succession planning and knowledge transfer. This is because we (Māori) see the future as part of the legacy continuum that was ignited in the past when the original kā was set alight.

This framework is still under development, and we are working to refine it through consultation with our whānau, hapū and iwi partners, and with our colleagues at Cawthron and across the research system. Our hope is that in sharing this now, it will prompt discussion and reflection that will lead to real change. We want to roll this framework out, and see it in action, and we look forward to sharing it when it is completed. In the mean-time, we encourage you to consider how you can draw upon these ideas in your work, and we welcome your thoughts and feedback.

We’ve also created a ‘Tāngata Tiriti’ checklist for researchers who are engaging with Māori, that could also be applied in a much wider social context by non-Māori anytime they are engaging with Māori. Here are some questions to ask yourself the next time you reach out to Māori for advice, ideas, suggestions or input:

-

- Whakapapa – Have you understood the connection between you, your organisation, and the Māori level of whānau, hapū or iwi you are engaging with?

-

- Rangatiratanga – Have you developed proper process to ensure mutual benefit and decision making?

-

- Manaakitanga – Have you ensured protection and respect for Māori knowledge and people?

-

- Ko te mauri-ora o te whenua kāinga – Have you considered the long-term, intergenerational benefits and requirements?

-

- Finally, a friendly reminder that if you are thinking of deriving commercial value from native flora and fauna, in the absence of any partnership with whanau, hapū, iwi or Māori enterprise, that needs to be considered in light of the Wai262 treaty claim and you should make sure you understand the claim and its implications.

4. Closing remarks

This might seem like a lot, but hopefully this article has helped you see why indigenous cultures that have been colonised deserve this amount of care and focus when considering how research can be just and equitable so that it benefits them. They are regularly being asked to contribute to the progress of science, therefore their aspirations should be central to the functioning of the science system.

Don’t overthink it, but think it over. You don’t have to share this perspective, but we’re asking you to try and understand and respect it.

The time is right to make a change, and we invite you to join us in making it happen because we believe this is the best path forward for Aotearoa and for everyone who lives here. When Tangata Whenua thrive, Aotearoa thrives.